My first 'Boss'

by Alfons Juraszek

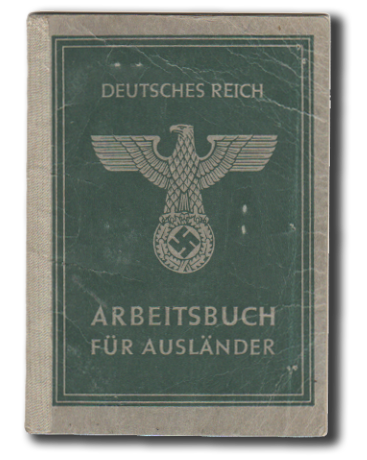

I have in front of me a twenty-page green booklet, half the size of a school exercise book. It has the German eagle with a swastika on its hard cover, the inscription DEUTSCHES REICH on top, and below ARBEITSBUCH FÜR AUSLÄNDER, or the foreigner’s work book.

I have in front of me a twenty-page green booklet, half the size of a school exercise book. It has the German eagle with a swastika on its hard cover, the inscription DEUTSCHES REICH on top, and below ARBEITSBUCH FÜR AUSLÄNDER, or the foreigner’s work book.

Trying to remember what happened thirty years ago, I reached for a dusty file of personal documents where, among all sorts of certificates, student identity cards and diplomas, I found my Arbeitsbuch. I have been keeping all these papers in the hitherto vain hope that one day they may come in handy, or at least refresh my memory. And so now I decided to write about my forced labour in Germany, if only to bear witness to those times of humiliation and to remember my murdered fellow slaves.

I don’t think that I had ever before looked so thoroughly at my Arbeitsbuch. It was issued on 23rd December 1943, when I was employed by old Wilk in Wirów near Gryfin. I remember that at that time I had received a message about my mother’s serious illness and asked my boss to get me a permit to go home. Old Wilk took some food, as a bribe, with him and we went immediately to Gryfin’s Arbeitsamt. They refused to grant me leave, but at least, after lots of footwork, issued me with the Arbeitsbuch. This was, indeed, a great success, as – so they explained to Wilk – I was on their black list as a “notorious criminal” and such people were never given any documents. It is only due to the efforts of that decent man, Wilk, that I am now in possession of this small book.

On the inside of the cover is an introduction which in translation reads approximately as follows: “Both German and foreign workers in the Great German Reich will contribute with their hands and with their minds to the rebuilding of Europe and to the struggle to improve the standard of living and the general wellbeing of the European nations. A foreign worker must always bear this task in mind, as his contribution and achievements at work as well as his attitude will depend on this.” Bearing in mind this guiding principle of the “General Commissioner for Labour” I fully understood why the Gryfin Arbeitsamt placed me on their black list. I was a dumb oaf, totally unaware of my role; I had no intention of contributing to the “better and happier future of nations”. This attitude and the absence of a correct way of thinking prevented me from reaching the designated targets, made me a “Schwarzpole” (a black-listed Pole), prone to “criminal activities”, such as attempting to escape. Old Wilk was perfectly aware of my attitude towards officialdom and must have been of a similar frame of mind, as he was always so well disposed towards me. It is unfortunate that he is placed sixth, i.e. last, in my workbook.

The honorary first place, entered on 18 February 1941, belongs to Heinrich Alisat, Neubarnimslow, Kreis Greifenhagen (the village of Barnisławiec near Szczecin). He was a German well aware of the tasks that Poles were meant to carry out in the Great Reich. It was he who taught me what slave labour and persecution of Poles in Hitler’s Germany were all about.

As most Poles, I was brought here against my will, in spite of what the Nazis were telling everyone. I am not sure whether this lie was meant to protect the “good name of the German nation” or some other bit of their propaganda, but the Germans went to a lot of trouble of trying to prove that they did not use slave labour, but that hundreds of thousands of Poles had actually volunteered for work in Germany and remained free employees. Signatures were collected by policemen in the regions with methods which brooked no opposition. In spite of it, particularly where there were large numbers of Poles – especially prisoners of war with their strong feelings of solidarity – there were people who refused to sign. But those were transferred to the penal camp in Police, where any resistance would be successfully overcome. I was forced in similar circumstances to sign a false statement. It is true though that a very small number of Poles did volunteer to work in Germany – mostly because they needed to escape from worse persecution by the occupier at home.

At the end of January 1941 my family was deported from Gniezno. We were first taken to the transit camp in Łódź, in Łąkowa Street if I remember rightly, where I was forcefully separated from my family and taken to Germany. As one of about twenty Poles I was taken under guard to Szczecin. In the local Arbeistamt a kind of cattle market was held. We were mustered along the wall of a building where farmers came to evaluate us, feeling our arm and shoulder muscles to asses our fitness for hard work. The first to be selected were tall, strong men. I was small and of slight build; there were no buyers for such a weakling. All the other Poles already left with their “owners”, while I remained unclaimed. Naïve that I was, I thought this might be a lucky outcome, perhaps I would get some light work, in a shop or an office.

Suddenly a tall, stout official called me. First name, surname, date of birth… When asked for my occupation I answered proudly: student. The man filled in his form, congratulated me on my German and reassured me that I would get a good job with Herr Alisat. Soon a thin, bald German appeared in the door, stretched out his arm in a Hitler greeting and reported to the official in an obsequious way. Having been told that I was assigned to him he looked disdainfully at my slight build and asked whether I was acquainted with agricultural work. My hopes for light work were gone. My explanations that I had never worked on the land made no impression, on the contrary, brought only abuse. I had to follow my master straight away.

We went by train to Kołbaskowo and from there three kilometres on foot. It was bitterly cold, I was frozen, hungry and so tired that I would have gladly lain down in a snow drift and fallen asleep. The road seemed to be endless. At last we arrived. I saw three identical farms, fairly close to one another; the first one on the left belonged to Alisat. We entered the kitchen from the yard.

While the family inspected me with unconcealed disapproval, the farmer, echoed by his wife, gave me a lecture on the subject of my duties, and what was expected of me and what was forbidden. Reveille at 5 a.m., then looking after the livestock, breakfast at 7 a.m., followed by work in the fields or farmstead, lunch, work, livestock etc… My boss was to be called “Herr” and his wife “Frau”. I was to eat in the kitchen by the chest of drawers; I was not to share the table with Germans. And what was even worse, I was not allowed to leave the farm without permission nor to let in any other Poles.

I stood there, helpless, in the midst of this German family, listening to the children’s contemptuous whispers of “Pollacke!” Tired and hungry, I could hardly stand up, but the farmer took me straight away to the barn, stable and pigsty. There were 10 cows, three old horses, three foals and a number of pigs, all waiting to be fed and their premises to be cleaned. My boss told me to find a fork and get rid of the muck. I found it hard just to bring in the empty wheelbarrow – it was heavy and too large for my thin arms, unused to physical labour. The huge fork would not fit my hands and however hard I tried, I could not lift the trodden down rotten and tangled straw mixed with cow manure. Sweat was pouring down my face, I could hardly stand up with fatigue, while the German kept shouting angrily, swearing and egging me on.

During supper my boss threatened that if I didn’t start working properly he would be obliged to beat me or send me to a punishment camp. He would not listen to my explanations that I had never done such work before, that I was weak after a night without sleep and a whole day without food. He decided that I was lazy and that my performance amounted to sabotage.

They gave me a thin blanket, a sheet, a pillow, an admonition to rise as soon as I was called, following which the farmer went to show me the place where I would be sleeping. Steep stairs led straight to the loft and on top of them was a concrete landing, roughly 2m X 6m. On the right hand side, under the slope of the roof, stood a plank bed taking up the whole space between the only wall (behind which was a room) and the banister surrounding the stair-well. Under the left slope of the roof lay a heap of corn. A sharp wind blew from the ill-fitting small window above the stairs and from the slits between the snow and ice covered roof tiles. I put down my bedding, looked at my filthy trousers, my water-soaked thin shoes and dripping socks and was overcome with a terrible loneliness. I desperately longed for my home, for my family, for my country. This feeling never left me through all the days of the war and of my torment. Within one day my whole life was turned upside down in a way difficult to imagine and I could not quite grasp that this was my reality and not some terrible nightmare. With a faint hope that the Germans would lose the war before the spring, wearing my jacket and my cap drawn over my ears, I lay down under my thin blanket with my coat on top of it, trying to sleep.

I could not foresee at the time that I would spend two winters in this forsaken attic. What I later learned to do was to leave my wet-through clothes in the stables, where they would at least have a chance of getting partly dry, and put a sack of straw in my bed. That little corner became the only place of peace and quiet, where I could get away from the hateful German eyes.

All the year round I was getting up at 4 a.m., sometimes even earlier. To begin with, Alisat would roar: “Aifstehen! Vier Uhr!” – get up, it’s four o’clock – but later I would rouse myself without it. By seven a.m., having seen to the livestock and eaten breakfast, I had to be ready for work in the fields or on the farmstead itself.

Already on my second day my master hit me in the face and from that time on he kept beating me with whatever and whenever he fancied. I could not even defend myself. He was tall and powerful and I just about reached his shoulder. One day Alisat burst into the cowshed screaming: ”You damned Pole, you haven’t fed the horses"! It’s sabotage! I’ll have you sent to the camp!” he kept cursing me, beating me all over with the fork. In fact the horses had been given their usual feed, which they had eaten before he came to look. I tried to explain it after breakfast, saying also that I was doing my best, but that if he was not satisfied he could send me back to the Arbeitsamt. Even before I finished he hit me several times in the face, grabbed me by the collar and dragged me to the stables. Three large, lean horses stood there. Alisat drew his finger over their rumps and declared: “They are covered in dust! Remember, my horses have to shine, they have to be cared for. I am a non-commissioned officer of the German cavalry and I’d be a fool if I did not make a proper groom out of you.”

Thus another task was added to my schedule. Every morning, while looking after all the animals, I had to polish his nags to a gloss, which was not actually possible, as old, ill-fed horses develop dandruff – and this gave the German another excuse for tormenting me.

One Sunday, after I finished all my tasks in the stables, cowshed and pig sty, my master graciously allowed me to meet some other Poles working in Kołbaskowo. As on wings I flew to the village on a path carved in knee-deep snow. I met some other Poles on the way and they took me to their place. The room was pleasantly warm, with a red-hot iron stove. I took the opportunity to get my clothes dry out properly; sitting there in my underpants I was happy as a child to be among welcoming fellow countrymen. We were so busy talking that we forgot about everything and meanwhile my shoes standing on the hot pipe began to smoke; luckily someone noticed it in time and saved them from going up in flames. All the same, the kind Poles gave me a pair of clogs, much too large, but I could wear them after winding some old sacking around my feet. Thanks to them I survived the winter unscathed, as Alisat did not pay me, telling me that he would buy me whatever I needed. But when I asked him to get me a cheap pair of clogs, he replied that I had not earned them yet. He also screamed at me and beat me for using torn old sacks as foot cloths.

In time my physical condition improved and I learned to work, yet I could never satisfy my boss. He only addressed me rudely, with curses such as verfluchte Schwein – damned swine, Hund – dog, Pollacke etc., beat me regularly and, worst of all, did not allow me to leave the farm. I was only allowed out to the fields to work and even then he kept checking that no other Poles came up for a chat. Over eighteen months I was allowed to go to the village only a few times. Even when another Pole working on a neighbouring farm came to see me, he would chase him away.

My first harvest on the Alisat farm began. Day after day, week-days and Sundays, I worked from dawn till dusk. And the nights in the stuffy attic under the hot tiles did not bring much relief. I wanted to sleep in the barn, but my boss would not let me, probably because I might have felt more comfortable.

I knew that I couldn’t count on conditions here getting any better, so I spent a lot of time contemplating chances of escape. And yet – contrary to all my careful planning – I was to act on impulse and not very wisely.

One autumn day the farmer beat me up badly during the morning jobs. I just could not stand it any longer – I dropped the fork and ran as I stood. Alisat did not even bother to chase me. How far could I get the way I was dressed, in trousers and shirt filthy with manure? I was so desperate that I did not give it another thought and just walked straight to Szczecin. It was only when I found myself in town that I realised that I did not know anyone here, that there wasn’t even any place where I could wash my hands. The very way I looked would arouse suspicion. I went to the Polish workers’ camp situated in an empty factory in Pomorzany, I looked around hoping to meet another Pole, but at this time of day people were either out working or asleep. I could not stay there any longer, as any minute now a policeman could come and arrest me. I walked aimlessly around for a bit longer, thinking how to get myself out of trouble, but found no satisfactory solution. Finally I decided to go to the Arbeitsamt and ask for a transfer to another farmer.

The same official who had dealt with me the first time round greeted me in a way which I should have foreseen: he shouted, he swore at me, and finally called a policeman to take me to the Gestapo.

By evening I was already in the penal camp in Police. According to the custom here, before a newcomer was registered, he was met by a ‘welcoming committee’, i.e. he had to pass through a narrow corridor on both sides of which stood SS-men and kapos, armed with whips, beating the victim all over his body. In the office one was given a number and assigned to particular quarters, where one had to report to the orderly, from whom one could expect another beating.

In the camp I was to some degree lucky; I was not treated any worse than the majority of prisoners, I might say that I preferred it to working for my farmer. But after the three weeks of my sentence were over, I was sent back to Heinrich Alisat.

And yet I could not stop thinking of escape. The time of the year was not suitable though, and I decided to wait till spring and meanwhile I did not stop planning. First of all I needed suitable clothes. With that in mind I wrote to various relatives. In the early spring an uncle sent me a striped navy blue suit. I managed to wheedle some money from my farmer and bought myself a small hat with a cord round it, as worn by local Germans. One of my Polish acquaintances, Heniek, nicknamed “Marynarz”, sailor, arranged for a German worker to buy me a railway ticket.

I did not go out for weeks, spending all the evenings and Sundays on the farm, usually working. I truly worked for two, gaining even Alisat’s approval; he was convinced that he had at last broken my opposition and brought me up to be a loyal slave. My tactics of throwing him off his guard proved so successful that he even tried to encourage me to become a Volksdeutsche; he considered me now as deserving of such an honour and, according to him, my name and place of birth denoted my German ancestry. I did not correct his misapprehension, as I needed his goodwill at this stage.

One Sunday my farmer asked me to deliver a letter to the burgomaster of Barnisław. On my return I told him that I met there a Pole who intended to become a Volksduetsche. This was of course untrue, but I needed an excuse to ask for a whole day off to visit someone in a location at least as distant as Barnisław. Alisat swallowed my lie and even kept encouraging me to visit this ostensible traitor. I pretended that I preferred to rest on the farm rather than walk such a distance and delayed my visit till Whitsun.

Heniek arrived on the Saturday before, telling me that everything was ready and that I could leave the following day. His German contact was to go to Szczecin in the morning to buy the ticket and bring it to Kołbaskowo where I could catch my train. To avoid any pitfalls while changing trains, I memorised the time table. I arranged with my boss that I would spend the whole day in Barnisław.

On Sunday I got up early, finished all my tasks on the farm and even brought some alfalfa from the field, and was ready to leave by 7 a.m. I unstitched the patch with the letter ‘P’ from my jacket and fastened it with pins, so it could come off at a moment’s notice. Wearing a decent suit and a German hat I started on my way to Barnisław, but past the hill I turned right instead of left to bypass the village and walk through the fields to the train station in Kołbaskowo. As arranged, the kindly German waited there with the ticket.

It was an anxious journey, but I negotiated all the control points and train changes and found myself in Gniezno by the evening. This was, according to my plan, only the first stage of my escape. I intended to proceed to Kraków, where my parents were living at the time.

I stayed in Gniezno for two months ad left taking with me a 15 year old boy, threatened with deportation to Germany. We had to change trains in Września, but there was a two-hour delay. Just as we were about to board the train we were stopped by the police and that was the end of the second stage of my escape.

As nothing else came to my mind, I admitted that I had escaped from Germany, but justified it by the fact that Alisat did not pay me at all for my labour.

I spent two months in prisons in Września, Poznań, Berlin and Szczecin. On 2nd September 1942 I regained my “freedom” and was assigned to my next employer in the village of Widuchowo.