Giesensdorf – Wittenbergesh

by Bolesław Stachowiaks

124 km north west of Berlin, between a small town, Pritzwalk, and the village of Giesensdorf, 1 km distant form it, lay a brickyard which was producing roughly 4 million bricks a year. It belonged to Karl Stamer, who also owned a large farm in the village. Its manager, acting also as foreman, was Hans Jank, a fat German who, as it in time transpired, had little knowledge of brick making. His only qualification for the job was the fact that he was unfit for military service. The raw material came from nearby layers of clay combined with a large admixture of sand and with large lumps of lime and was brought to the surface by a big mechanical digger.family

In November 1939, scarcely a month after the calamitous September campaign, I found myself in the first transport of forced labour to Germany organised by the Poznań Arbeitsamt. There were 14 of us, all from Poznań, nearly all young men, and the whole group was taken to that particular brickyard. We were assigned quarters in a small one-storey building, where we slept in two-level bunk beds on straw-filled palliasses. The dormitory was heated by a tile stove. Our food came from a separate kitchen and was cooked by a specially engaged older German woman; it was reasonable to begin with, but got progressively worse.

In Germany brickyard work was classified as heavy and thus the food rations for brickyard workers included certain supplements. This, however, lasted only as long as we worked together with German workers, just few of whom were left, their task being to train us in the difficult profession of brick making. The work included working in the clay pit, where it was always incredibly muddy, whatever the season and weather. We were not provided with work clothes other than the essential high rubber boots. We worked for eight hours a day without a break and had a meal after work.

Getting used to working with a spade and a pickaxe took me some time. My hands had to harden. Looking at them later I had a fleeting thought that had I tried to stroke a child’s cheek, it would make it cry.indu

As Poles were learning the trade, the remaining Germans were being called up one by one. In time we accounted for all of the brickyard workforce, with just a few exceptions, such as the kiln and the main machine operators. In time our Poznań team was joined by a group of about a dozen Polish workers from Mogiła, near Kraków, the area of the present day Nowa Huta (a post-war industrial town near Kraków). They were true craftsmen with experience of manual brick making, much better versed in the trade than was our foreman not to mention us, men from Poznań. Several highlanders arrived later too.

Being fluent in German, I often acted as interpreter for the foreman. One day he announced that a thick layer of sand had to be removed from the clay pit as soon as possible, as it was impeding the exploitation of clay. He offered to pay one mark for each dumpcart of sand removed from the clay pit to a designated place. Having made sure that his promise would be fulfilled, our brick makers from Mogiła organised the job in such a way that the full dumpcarts were moving down an incline under their own weight, and only the empty ones had to be pushed back to the pit, where they were filled up again with little effort. Our foreman kept watching this operation with amazement and must have come to the conclusion that there were people here who knew much more about the trade then he did. But he did pay up as promised.

Something similar happened with lime, which is an unwanted nuisance in clay used for bricks. He again offered one mark for each bucket of lime separated out in the pit. It was surprising how much lime was suddenly found in the clay. The buckets having been checked by the foreman, the lime kept going back to the pit in empty dumpcarts… and the foreman was paying up.

We also managed to supplement our inadequate food rations in a variety of ways. Potatoes were easily obtainable and our metal workers produced a grater, first a manual one, but mechanised later by having it connected it to the general transmission serving the brickyard machinery. Potato pancakes were then mass produced on the innumerable hot apertures of the kiln. The latter were also used to cook the small beans filched from the easily accessible stores, where a supply was kept as seeds to be grown for animal feed. Our foreman, who lived with his wife in a house on the factory grounds, kept a large number of chickens, but the places where they laid their eggs were best known to the forced labourers.

Crudely made shoes worn by some forced workers.Our footwear was the greatest problem. Shoes brought from home were rapidly wearing out and it was impossible to spend all day in rubber boots. A remedy was soon found. Our metal workers had easy access to the stores where they discovered a worn-out machine leather belt. The belt kept getting shorter, while we had a good source of sole leather.

Crudely made shoes worn by some forced workers.Our footwear was the greatest problem. Shoes brought from home were rapidly wearing out and it was impossible to spend all day in rubber boots. A remedy was soon found. Our metal workers had easy access to the stores where they discovered a worn-out machine leather belt. The belt kept getting shorter, while we had a good source of sole leather.

Our compatriots working on neighbouring farms proved also very helpful. Eggs, bowl of curds, even butter, would find their way to the brickyard.

An elderly German by the name of Schrantz was the local gendarme. I gained his goodwill for our whole team by acting as his interpreter, not only in the brickyard, but in the entire district. He got me to accompany him to nearby localities. This way I got to know the whole Polish workforce in the area.

Polish family conscripted as forced labour in Germany.In one of the villages I met two Polish families with children who came from the Gostyń district. They had been expropriated there and deported to Germany, while their large farms were settled by Germans. The whole Polish families were now working on German farms, where they were paid in agricultural produce. The Gostyń district had been known for its high class agriculture and now these families demonstrated time and again that their agrarian culture was much superior to that of their employers. I remember those truly cultivated people with great pleasure and I used to meet them again, many years later, in the new post-war Poland, when they would help us greatly by providing us with bread.

Polish family conscripted as forced labour in Germany.In one of the villages I met two Polish families with children who came from the Gostyń district. They had been expropriated there and deported to Germany, while their large farms were settled by Germans. The whole Polish families were now working on German farms, where they were paid in agricultural produce. The Gostyń district had been known for its high class agriculture and now these families demonstrated time and again that their agrarian culture was much superior to that of their employers. I remember those truly cultivated people with great pleasure and I used to meet them again, many years later, in the new post-war Poland, when they would help us greatly by providing us with bread.

Karl Stamer, the brickyard’s owner, had two sons, one served in the Wehrmacht, while the other, a one-armed invalid, administered the brickyard. The father was a typical Prussian, who considered us all as subhuman, and his sons were not much better. Confrontations with the workforce were quite common and the Stamers often used their guns as a deterrent. The invalid son was particularly brutal. In a neighbouring village where Stamer owned another estate of several tens of hectares, this son had an argument with a Russian woman, a forced labourer, and a teacher by profession, and beat her to death with a cowhide whip. Even the local Germans were shocked, but he was not punished until later, when the area was occupied by the Soviet Army. The commanding officer was informed of the case and after a brief court martial the man was condemned to death and executed. Even his compatriots did not mourn him.

When one of our people caught a chill and, suffering from exhaustion, died in hospital, and we were making arrangements for his funeral, we discovered that Stamer had forestalled us by trying to order from the local joiner a ‘Pollackensarg’, a particularly shoddy coffin. He was told however that all coffins were the same, whoever the deceased was. Eventually, we ourselves ordered the coffin, as well as a brick cross with a Polish inscription. He was buried at the Giesensdorf Catholic cemetery with the assistance of the local priest.

As our area lay below the flight path of British and American bombers, we often saw leaflets and incendiary bombs being dropped. Those bombs, shaped like large portions of ice cream in a waffle, were dropped at night and burst into flames automatically and noiselessly two hours after sunrise. The contents of the leaflets varied. For instance, a single page leaflet showed on one side a heap of German Iron Crosses of all classes, and on the other a huge cemetery with white grave crosses – without any comment. Another showed a typical page of the Völkischer Beobachter with a picture of Goebbels, accompanied by an excerpt from one of his propaganda speeches, stating that the world must be prepared for every German family to sacrifice one member on the altar of war. This was meant to show the Germans how light-heartedly Goebbels was prepared to send to death eight million of their people. Yet another leaflet, dropped towards the end of the war, warned all Germans employing foreign forced labour, that after the war any ill-treatment of these labourers and prisoners of war would be punished with all the severity of the law. These leaflets assiduously collected and destroyed by German authorities, made a great impression on the German population.

We were well informed about the current situation on all the fronts, as the Germans forgot about a radio left in former German recreation room. The German workers were no longer there, but we eagerly listened every night to the Polish broadcasts from London. We delighted in the highly significant news about the Nazi defeat at Stalingrad. The Germans who used greet one another with the salute "Heil Hitler” changed now to “Grüss Gott”.

We were 124 kilometres distant from Berlin, but we watched from the rooftops the nightly air raids on the city, though all we could see were the magnificent light effects.

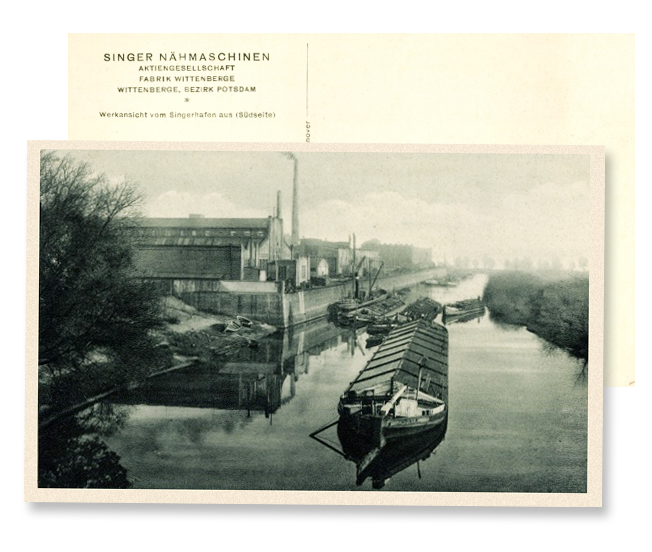

Nähmaschinenwerk Singer AG - WittenbergeTowards the end of 1943 the brickyard workforce was reduced after several Poles were transferred to various factories in the neighbouring towns. I found myself in the renowned Singer sewing machine factory (Nähmaschinenwerk Singer AG) in Wittenberge on the river Elbe. This factory employed workers from all the conquered nations as well as prisoners of war – British, French and Italian. The Italians were treated worse than the rest. The workforce also included many Dutch, Ukrainian and Polish women.

Nähmaschinenwerk Singer AG - WittenbergeTowards the end of 1943 the brickyard workforce was reduced after several Poles were transferred to various factories in the neighbouring towns. I found myself in the renowned Singer sewing machine factory (Nähmaschinenwerk Singer AG) in Wittenberge on the river Elbe. This factory employed workers from all the conquered nations as well as prisoners of war – British, French and Italian. The Italians were treated worse than the rest. The workforce also included many Dutch, Ukrainian and Polish women.

We were housed, each national group separately, in wooden barracks erected in the factory park. Polish workers were usually assigned to particularly dirty jobs, in the foundry, in mould cleaning, etc. The Polish group consisted of about 20 men, mostly young, and 20 women. Our barrack was close to the railway station, which was also one of the barrage balloon anchor sites, and this added to the risk during air raids. British and American bombers were flying overhead practically every night. Following an alarm most foreign workers, particularly prisoners of war, ran into the fields. We did the same to begin with, but later, used to it, we mostly went on sleeping.

Amazingly, Wittenberge was left intact almost to the end of the war. At noon of the first day of Easter 1944, on a beautiful sunny day, a large formation of bombers flew overhead in a direction different than usual, towards Poland, we thought. Unfortunately we were right and, as we learned later, Poznań had badly suffered. Eventually, at the beginning of 1945, also about noon on an ordinary working day, a large British formation dropped incendiary bombs all over Wittenberge, but particularly on the Singer factory. Everything went up in flames: huge stores of raw materials of the neighbouring artificial fibre factory, our factory’s stores of beech timber for the sewing machine tables and the four-storey stores of hard wood veneers. In spite of the non-stop attempts to extinguish the fires with vast amounts of water, they kept burning for several days until everything turned to ashes.

A month later we experienced another, even more frightening, air raid. The allies were determined to disrupt the railway connection between Berlin and Hamburg, Wittenberge being half way between them. After the all clear we learned that the railway station and the four-track railway line were totally destroyed by bombs of a particularly high destructive power, which left craters two metre deep all along the line. The torn and mangled rails, coiled like springs, stood together with sleepers up to 10 m high. The gravel of the tracks got thoroughly mixed with the coal thrown out of hoppers. The neighbouring allotment gardens suffered in a very odd way. Fruit trees were uprooted, but coming down they turned over and stood now on their crowns. The concrete highway leading to the station had turned on its side and gave the appearance of a wall. A railway engine, cut exactly in half, looked like an exhibition model. It all made such an eerie impression, that I shall remember it as long as I live.

Our basic food was bread, but we were given insufficient rations. Help came from Poles working in the local bakeries. They were giving us ration cards which we could use to buy bread in other shops. Dutchmen working in the local oil mill brought us edible oil.

In mid–1944 the Germans started spreading false information by way of propaganda news-sheets in Polish, which we nicknamed the "reptile press". I tried to counteract this propaganda through evening talks in the barrack. The Germans inserted a Polish-speaking informer into our barrack, who eagerly passed on all the information to the police. As result in August 1944 I was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to an Arbeitserziehungslager, or the penal camp in Grossbeeren, near Berlin.

From there, on a starvation diet, we were taken every day to earth works on the construction of the marshalling yard in Berlin. This was truly hard labour. Occasionally, with the help of a German railwayman, one could smuggle a postcard home. The prisoners were all forced labourers of many nationalities. The guards treated us in an exceptionally brutal way and for a minimal transgression beat us about the head with a special cane. A typhus epidemic broke out in the camp, but luckily I did not succumb to the disease. The dead were buried by the prisoners in the manner typical of concentration camps. A task unit of prisoners would dig common graves about 2 km from the camp. Other ones, using a special hand cart, would twice a week take out about 20 bodies placed in primitive coffins. The bodies were then shoved naked into the graves and the coffins taken back to the camp for re-use. The graves were sprinkled with lime, then covered with earth. Everything was done by prisoners.

I was released from the penal camp in December 1944, just before Christmas. When I returned to my barrack at the Singer factory, my old mates took me for a spectre – being 183 cm tall I weighed only 48 kg. Slowly, caringly helped by my friends, I began to feel better and recover some of my health. As I learned later, the informer who had grassed on me was so severely beaten on several occasions that he was eventually withdrawn from our barrack.

Towards the end of 1944 the Germans became somewhat more benign towards us. They even let us celebrate Christmas in the factory recreation hall. We sang Polish songs, recited appropriate poetry. The guards were, of course, present.

All these events rekindled our hope that our misery was coming to an end. The American Army was approaching Wittemberge from the west. One day we could clearly hear guns. The following day several series of automatic gun fire brought down the barrage balloons and we expected the Americans to reach us by the morning.

However, it did not happen this way, as the Germans decided to evacuate the camp to an area still in their possession. We were moving eastward under guard, spending the nights in barns of local villages. The cannonade could be heard all the way. There were problems with the food supply, but Poles working on nearby farms brought us during stops whatever they could: potato pancakes, cooked potatoes and milk. We shared that food with other nationalities too.

After several days of wandering the column approached the area I knew, in the vicinity of the brickyard. One night in April of 1945 the village we had stopped in for the night was taken by the Russian cavalry. The Singer factory guards ran away.

Having learned who were we, the Soviet commandant made sure that we had enough to eat, gave us bread and tinned food and asked what our intentions were. Told that all we wanted was to return home, he had no objections and assured us of the goodwill of the Red Army. We broke up into groups according to nationality, all determined to make their way to their respective countries.

I gathered all the 14 Poles from our barrack and we set out to the brickyard, several kilometres away. We stopped in Giesensdorf, the village where I knew Karl Stamer, the brickyard owner, had a small estate. The village was already in Soviet hands. During the night which we spent in a barn Soviet tanks had occupied the nearby town of Pritzwalk and in the morning we began to prepare for our journey home. First I made the estate manager give us food. We got a fattened pig, potatoes and milk. The next priority was to organise baths and laundry. Then, clean and no longer hungry, we discussed how best to get home.

Using two oxen we managed to drag a heavy Dreutz tractor converted to wood gas from a nearby swamp. The Germans pushed it there deliberately to avoid it being confiscated. We cleaned off the mud and gained our means of transport. We also prepared two trailers, loading one with the fuel, i.e. finely chopped wood. Women, children, the weaker ones of us and luggage went on the other one. The fitter ones rode bicycles, which Soviet soldiers gave us, having confiscated them from Germans. And so we started our return journey to Poland.

We got to Berlin on 7th May 1945. The German capital was on fire. We watched with great satisfaction the long columns of German prisoners of war of all ranks and all formations, often guarded by soldiers in four-cornered caps, so typical of the Polish uniform. Further on we got lifts on lorries going east, sometimes carrying ammunition or explosives. The hospitable soldiers often shared their food with us.

At long last we reached Ścinawa, where we learned of the army transports going to Poznań. On the evening of 8th May 1945, with the transport commandant’s permission, we got on to the open railway platforms carrying damaged Soviet tanks; we spent the night lying under them.

We arrived in Poznań on the morning of 9th May 1945.

Seeing devastation and smouldering ruins everywhere, I was concerned for the fate of my family. Having cleaned up at the station I left my group in the hands of the repatriation officer; this would secure care and food for them and free railway tickets for their return home anywhere in the country.

I found my wife and our son –already seven years old – in good health and happy to have their husband and father back.