I was nineteen at the time

by Janina Dębicka-Malińska

On 23rd February 1943 I came to share the fate of the thousands of Poles deported to Germany for forced labour. I was 19 years old. I was taken from the village of Nadolany in the Sanok region of the General Gouvernement. In our locality the deportations were not based, as in other places, on street round-ups, but the village headman would be given the list of names of people selected for work in Germany and was obliged to provide the required contingent. The Germans threatened to set houses on fire and confiscate the livestock, should the quota not be met.

My father, Jan Dębicki, was not a farmer, but a shoemaker. He had 10 children and a sick wife. I was his sixth child and the fifth daughter to be sent to Germany. Only the youngest siblings and my poor, sick mother who worried about us all, remained at home. She had already experienced the pain and despair of parting, when before the war in Poland her oldest son had to serve a two and a half year prison sentence for communist activity. That same brother, Tadeusz, was hardly ever seen at home in the years of occupation. The Germans were ceaselessly searching for him and, being unable to lay their hands on him, were taking, one by one, those of us who had reached adolescence. Two of my sisters, Józefa and Władysława, found themselves thus in Berlin and my 17 year old brother, Zygmunt, was in Hanover. Another sister, Genowefa, had been deported to a health resort in the Harz mountains, but managed to escape after two years and return home. Not long after, the Germans deported her again, but she ran away for the second time, this time jumping from the train in Jasło. The police were seeking her, but to no avail, while she managed to stay at home in hiding. She was helping our sick mother to cope with all the problems that daily life brought in occupied Poland.

The moment of parting arrived, and with it the family’s despair and my fear of an uncertain future. I was taken to Sanok and from there to Jasło. We were mostly young men and women, but there were also people in their thirties. We were being taken to Kraków, but when on the way the train stopped near Ojców, few dare-devils jumped off the poorly guarded train and ran towards a nearby forest. The Germans began shooting, but the fugitives disappeared in the thick vegetation. The thought that some people don’t give in whatever the circumstances, filled me with new courage.

In Kraków they kept us imprisoned for about three days. We slept on wooden bunks and were given black coffee, bread and ersatz honey once a day. They also carried out a disinfection and delousing; we had to take off all our clothes, including underwear, and these were taken away for processing. Meanwhile we had to stand naked, in groups of four, while the male guards kept leering and taunting us. We were greatly shocked, but this performance was to be repeated again in Germany. I also remember a nasty incident in Kraków. There were amongst us some Highland girls of outstanding beauty. Two of them went mad, crying, screaming, pulling their hair. The Germans took them away and we never learned what happened to them.

During the journey from Kraków through Silesia we passed huge glowing lights, looking alarming against the night sky. They were steelworks, which I, a country girl, had never seen before.

We arrived in Ulm and were led to barracks across the town. I noticed on the way a huge church steeple and it was only years later that I learned that it was a world famous cathedral. The worst moment came in the barracks. These were huge halls, former warehouses or stores with a concrete floor, on which lay smelly, disgusting pallets for us to sleep on. It was incredibly cold and we had to put all our clothes on in layers, one on top of the another. In addition we had to keep running and exercising to keep warm, it was after all a very cold February. And again we had to undergo the process of disinfection, the same as in Kraków.

Next they loaded us into cattle wagons together with men; we all had to stand, there was so little room. After a long journey they left our wagon in a siding for 10 hours. Tired out, I could no longer stand, the pain made me grind my teeth. We tried to maintain some dignity, but locked in this car we could not refrain from satisfying our basic needs. It was a great relief when our car was attached to another train and we were on the move again.

We found ourselves in Überlingen, the capital of the administrative district in Baden, and on arrival were taken to the Arbeitsamt. I am writing “we”, in plural, as I found myself together with my school mate, Władysława, or Władka, Dąbrowska. She had lived not in Nadolany, as I did, but in Nowotaniec, where our school was. She had been in tears all through our journey into the unknown and I, unable to cry, was trying to console her the best I could. Now we reached the end of our travels. Local farmers, notified by the authorities, began to arrive and pick their labour. One of the deportees acted as interpreter. She mentioned that one farmer required two women workers. I did not want to miss this chance, I grabbed my friend’s hand and said: ”Come on, we shall be together and at least we shall not be made to work in a factory.” I was terrified of air raids and of hunger in a town, besides I was used to country life.

A young German put us on his cart and we rode with him for several hours, until we reached his farm in Hohenbodman. It was evening by then and we were exhausted by all our travelling and the nervous tension of the last few days. As we soon discovered, there was already one Pole working here – he was Antek Padoł, a boy of 18, from the Kraków district. He could already speak German, so the farmer’s wife had no difficulty in communicating with us. She took us to the kitchen and, following a quick wash and meal, showed us to a tiny room on the other side of the corridor. It had no means of heating. In spite of the cold we went to bed straight away, at last being able to rest after the long days of torment and fear of what the dreaded future had in store for us.

At 5 a.m. a knock on our door accompanied by “Guten Morgen” pronounced in a drawn-out throaty way got us out of bed. We dressed quickly and joined Antek waiting for us in the corridor, and followed him to the stables. Our German mistress instructed him that we were to milk the cows, which was not a problem, as we were used to this kind of work. Władka was better at it than I, as her family owned a cow. Once we got into the stride, we quickly milked three or four cows each, even though our wrists ached to begin with. There were ten cows altogether and all the milk, apart from a small amount left in the house to be drunk with coffee, was taken to the dairy.

It became one of my duties to take the large churns of milk in a hand-drawn cart the 100 metres to a particular point, where all the milk from the village was collected and taken to Überlingen. After our morning tasks in the cowshed, pigsty, stables and chicken coop were completed, we sat down to breakfast. We were, surprisingly, sharing the table with the whole household, consisting of the farm owners, Maria and Wilhelm Föll, both in their forties, their little daughter Bärbel, an old German farm worker by the name of Mesner, and the three of us Poles. I was shocked by the way breakfast was served: we all ate from one saucepan containing what looked like noodles made of rye flour, with melted butter. This was accompanied by bread and milky coffee.

After breakfast they asked us, again with Antek’s help, where we had come from. But no respite was given us in spite of our nightmarish journey and we were sent straight away to our multiple tasks.

We were free in the evenings, in the winter after 8 p.m. and in the summer later, depending on the seasonal work, such as haymaking or harvesting. We were on our feet all day, sitting down only for meals. And so our days were filled with labour, often beyond our strength, with sorrow at our hopeless fate, with longing for our families and homeland. Letters were our only comfort; I wrote them in the evenings, I described my longing, I waited impatiently for replies. I corresponded with my parents and friends at home, with my siblings deported to Germany and with the boy left behind, my darling, the first shy love of my young life. Longing was a kind of illness, as I learned during those hard years.

Apart from my difficult, sad daily life, there was another side to the struggle: I had to maintain my dignity, my dignity as a human being and my dignity as a Pole. To begin with it must have been an unconscious battle, but later, provoked by Frau Föll who became aware of my hostility, it became quite open, though I paid a rather high price for it. We had come to this farm as a twosome and Maria Föll did everything to create a rift between me and my friend. She openly favoured Władka, giving her all the easy jobs, the household ones in the winter, while I had to perform all the nasty, cold and dirty ones, like cleaning the pigsty and taking the dirty litter out by wheelbarrow, collecting potatoes for fodder, cooking them, etc.

Back in the house after my outdoor work I tried to be particularly nice to Władka, pretending I did not notice our mistress’s manoeuvrings.

An incident took place during haymaking in the spring of 1943. It was a sweltering day. Together with Frau Föll I was spreading the mowed grass to dry. I tried to work fast, but in spite of it I could feel the prongs of the German’s fork constantly pricking my bare heels. My pace changed, I was now almost running. Panting with heat and the speed of work, bathed in sweat, I felt I could not hold out much longer, but my slave driver did not give up, jabbing me again and again with her fork. Finally I could bear it no longer. I stood up, aimed my fork at her, and swore at her in Polish: “You bloody old witch, I shall skewer you if you don’t stop!” The woman jumped to the side having guessed the gist of my words, then took my place and I took hers. We continued working as if nothing had happened. Władka and Antek were horrified. “What have you done? Don’t you understand, it may cost you your life if she denounces you to the police.” She didn’t. I think that she was testing me and by her magnanimity wanted to abate my hostility towards her. This incident was to help her in the future, while haymaking was always linked for me with it.

An incident took place during haymaking in the spring of 1943. It was a sweltering day. Together with Frau Föll I was spreading the mowed grass to dry. I tried to work fast, but in spite of it I could feel the prongs of the German’s fork constantly pricking my bare heels. My pace changed, I was now almost running. Panting with heat and the speed of work, bathed in sweat, I felt I could not hold out much longer, but my slave driver did not give up, jabbing me again and again with her fork. Finally I could bear it no longer. I stood up, aimed my fork at her, and swore at her in Polish: “You bloody old witch, I shall skewer you if you don’t stop!” The woman jumped to the side having guessed the gist of my words, then took my place and I took hers. We continued working as if nothing had happened. Władka and Antek were horrified. “What have you done? Don’t you understand, it may cost you your life if she denounces you to the police.” She didn’t. I think that she was testing me and by her magnanimity wanted to abate my hostility towards her. This incident was to help her in the future, while haymaking was always linked for me with it.

A major headache in my daily life was the problem of clothes. The ones I brought with me were wearing out with the hard work in the fields and even more so in the stables. I did not know any Germans who would be willing to sell me things. I was paid a small monthly wage, but as a forced labourer I had no right to purchase clothes in shops. So I spent my money on writing paper and some trivia, reasoning that marks would not be worth anything when the war ended. I wrote home, as well as to my sister in Berlin, asking for any old garment, and they did help to a degree. But I lacked everything, from underwear to warm outer clothing for the autumn and winter.

Winter was the worst time for the paupers that we were, working outdoors in the cold for hours. For instance one had to load and push wheelbarrows full of beet as fodder for the cows. This often brought tears to my eyes. I was stiff with cold in my inadequate attire, my arms ached from the heavy loads – and this had to be done twice a week, at least 20 barrow-loads each time.

Some Polish prisoners of war were also working in our village and in the neighbouring ones. They had been thrown out of their prisoner of war camps, deprived of their prisoner of war status and made to work for local farmers. Having been brought to Germany soon after the outbreak of the war, they had mastered the language by now and managed to listen to radio broadcasts and shared the news with us. It helped to keep our spirits up. We used to meet on Sunday afternoons in a barn where one of the men had his lodgings. The German owners of farms, fearing reprisals from their own authorities, were generally not happy about groups of Poles getting together. But this barn was not too close to the farmer’s house, we were not too visible, so we continued to meet there.

The men had belonged to all kinds of social groups and were of different ages. There were also some young boys deported in the same way that we had been. They had their own band and were delighted to have us, girls, to dance with. But though we did not really enjoy dancing, exhausted as we were by the hard daily work, we did not know how to excuse ourselves – thus even the entertainment felt as if forced on us. There were also three Russian girls working in the village. One of them, a Muscovite, used to be a university student.

The men had belonged to all kinds of social groups and were of different ages. There were also some young boys deported in the same way that we had been. They had their own band and were delighted to have us, girls, to dance with. But though we did not really enjoy dancing, exhausted as we were by the hard daily work, we did not know how to excuse ourselves – thus even the entertainment felt as if forced on us. There were also three Russian girls working in the village. One of them, a Muscovite, used to be a university student.

Meanwhile things were happening in the wider world. The allies were ever more frequently bombing German towns and cities. Many people dislocated by the devastation were being sent to the country and thus a family of five came to stay on Wilhelm Föl’s farm. They were a middle aged couple, with their mother and two teen-age children. The Germans were beginning to feel threatened now, but did not want foreign workers to see it, particularly as their despair was our joy. Our mistress was increasingly bad-tempered and we were an easy target.

There was a lot of work in the summer, both in the fields and in the house. Planting potatoes and beets, haymaking and harvesting followed one another and kept us busy from 5 a.m. till 9 or 10 p.m. With washing, mending our clothes and letter writing we hardly ever went to bed before midnight, thus never getting more than five or six hours sleep.

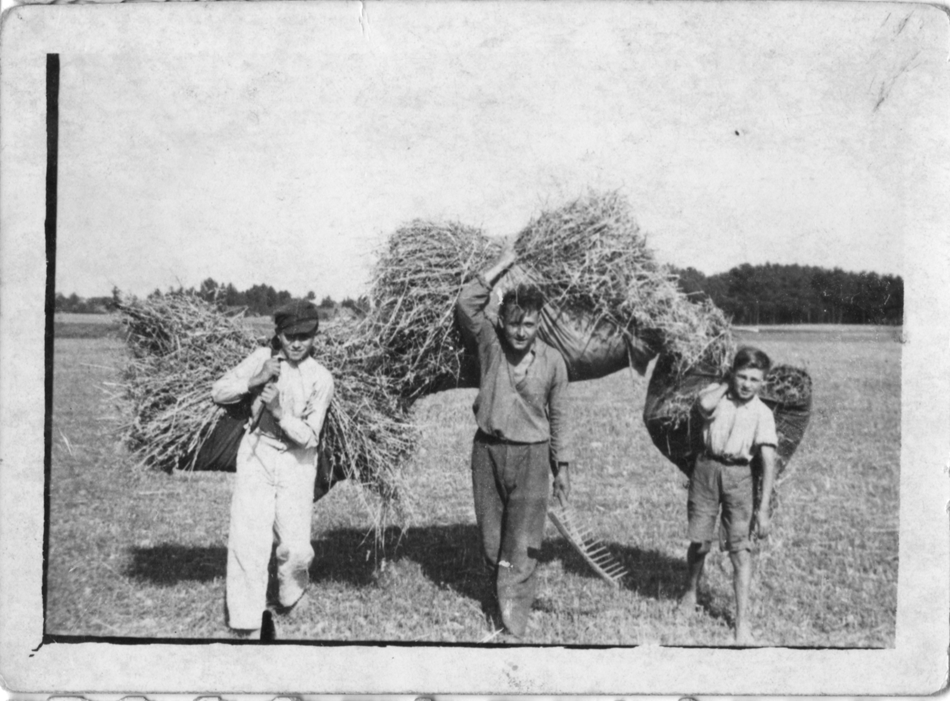

Polish boys conscripted to work on German farmsI shall always remember my first haymaking. The heat was unbearable and we would go home for lunch about midday. Frau Föll would choose Władka to help in the kitchen, while I would be sent to spread the grass in the loft to dry. I could hardly breathe under the scorching roof and was so exhausted after an hour’s work in this blazing hell that I was not even able to eat. My mistress screamed at me in fury: “You have to eat, you damned girl, or you’ll be too week to work!”

In the evening, after a day’s work in the fields, we had to look after the livestock. One day, following a hard day’s haymaking, I went to milk the cows, when I was overcome by a serious nose-bleed. They lay me down and put a cold compress on the back of my neck.

I actually often longed to be taken ill and be given some rest. Once I was off work for three days. Following a cold, I developed a huge abscess and had to stay in bed. My mistress herself treated me with hot linseed poultices, so that I would again be fit for work. I dreamed of a time when I could dispose of my own time, do what I fancied, rest when I chose. Instead I was made to work all hours of the day in the fields, the woods, the orchard and the house.

The only recompense was the beauty of the area. Baden, lying in the foothills of the Alps, looked like a backdrop to an enchanted dream.

I was becoming more and more the object of Frau Föll’s persecution. One day a whole ham left to cure in the cellar disappeared. I suspect that the woman lodger took it for her family. But I was accused of stealing it, sending it to my sister in Berlin, and was threatened with the police. I complained to my Polish friends and one of the boys who worked for the village headman repeated the story to him. The headman called my mistress and told her that I had lodged a complaint. This blew over, but not for long.

One day, while busy doing the laundry, Władka and I noticed with glee how much dirtier the Germans’ bed linen was than ours. But Frau Föll grabbed a pair of my knickers and started laughing: “And where did you get these? They are men’s underpants, not ladies’!” I replied that my sister had sent them and that only their cut was similar to men’s. An increasingly vicious exchange followed. In the end she, of course, won and as punishment forbade me to share the warm room in the house. I had to stay in my unheated room, with hoarfrost on the walls, writing letters sitting in my bed with all my clothes piled on top of me. No wonder that both Władka and I developed rheumatic pains. Maria Föll took us to the doctor in Überlingen. He gave us some painkillers, but the rheumatism continued to plague me in various stages of my life.

One wet day old Mesner and I were sent to spread some artificial fertiliser. I don’t remember its trade name, but the instructions required the wearing of masks and protective clothing, which we did not have. Soon I felt a burning sensation in my hands and eyes. The drizzle changed the dust on my face into a hard crust. I cried, but did not stop working. Back in the house I was told to wash my face with olive oil, but the crust remained unbroken and my eyes looked terrible. The crust on my face changed into a scab and remained unbroken for over a month. Luckily it left no permanent scars.

It was now 1945 and the 9th May of that year was the happiest day for millions of people – myself amongst them.

We were liberated by the Foreign Legion on 5th May. There were Poles and sons of Poles among them, they spoke our language, and kept asking us how badly treated by the Germans we had been.

But none of us were looking for revenge.