I shall be back, mother!

By Jerzy Walczak

In September 1939 the Germans occupied my undefended home town, Koło, without struggle. In the first few days they arrested over a dozen men of the Polish intelligentsia, including Mr Orywol (or Orywal), whom I knew, as he was the head of the road department and thus my father’s superior. Mr Orywol lived in the nearby village of Dąbie. The men were executed in the Chełmno area of the Koło district, where a memorial had since been erected bearing their names; a large obelisk was also erected to commemorate Jews murdered there by the Nazis. Apparently the list of Poles to be eliminated was already prepared before the war by local German inhabitants (the so-called “Fifth Column”).

One of those Germans, by the name of Lauf, owned a food shop and a large building at Sienkiewicz Street in Koło. My father often bought some food there on credit (not unusual at the time). Lauf was quite happy to let him do it, but when my father was unable to repay it all at once, he threatened him with either legal proceedings or demanded we handed over our only cow, the mainstay of our survival. Father was terrified of courts, so there was no other way, he had to forfeit the cow.

After the Germans occupied Koło, Lauf became even more insolent and kept accusing father of owing him more money. One day, when father was passing his house, Lauf came out aiming a pistol and threatened to kill father unless he gave him a particular sum of money. Father borrowed 50 złotys and told me to take the money to the shopkeeper. As I was handing it to his wife, she sneered: “Now that Poland is ours, your father has no difficulty finding the money, has he?”

In the late autumn of 1939 armed German soldiers were escorting groups of Polish prisoners of war through the town. Some of them limped, some were lacking shoes, others had their heads or arms swathed in bandages. They marched with their heads down, cold, hungry, unshaven. My younger brother and gave them our last crusts of bread.

That same autumn the Germans got all the Jewish men to work on the construction of a bridge on the river Warta. I saw how they were forced to get into the water in their traditional black gabardine coats. Exhausted and shivering with cold, many of them drowned.

In the spring of 1940 we were expelled from our flat and moved to another one in Toruń Street. It was much worse. It had no garden for growing food, it was cold and dilapidated, overrun by mice and rats.

My two sisters took jobs as chambermaids in the local hotel, Deutsches Haus. Bolek, my eldest brother, was taken by the Germans with a road construction team to work in the east. Having fallen ill, he returned several months later.

One particularly shocking event of 1940 engraved itself on my memory. In Powiercie, in the district of Koło, the Germans found a hunting gun in a Polish home. The owner was taken to Koło, whose inhabitants were deliberately rounded up to watch, put against the wall of the town hall and shot. I ran there having heard the salvo. The body of the man lay by the wall, his head shattered. German soldiers dragged the body by the legs along the street, threw it on the waiting cart like an animal carcass and drove away. It happened either in the late spring or early autumn of 1940, I do not remember the exact date. But it shook me to the core.

In the early spring of 1941 I alone of the whole neighbourhood received the summons to the German Labour Office. My family and the neighbours were all dismayed, wondering what I was wanted for. My father grabbed my hand and took me to Herr Baumgardt, the manufacturer of concrete roofing tiles, at the corner of Kolejowa and Toruńska Streets. Before the war in his free time my father quite frequently worked for this man to make some extra money and hoped that in view of the old acquaintanceship he could count on his help. “He might even find you job in his factory,” father said. But he was disappointed. “Oh, no!” said Baumgardt. “Times have changed, I see no reason for helping you people now!” Disgusted, father spat on the ground and we left.

Three days later I had to report to the Arbeitsamt. My sister, Janina, who knew some German, came with me. A German female clerk took my details and told me to come back in a week’s time with personal belongings and food for two days. It thus became obvious that I would be deported, but this time I was still allowed to return home.

Our neighbours kept solicitously asking me questions. Father’s friend, Mr. Borucki from the village of Ruchenna, gave me a length of cloth for a suit, and a neighbour, Mrs. Józefowicz, made it up for me in a hurry. Mr. Świder made me a pair of clogs of alder wood – they were particularly light. Bolek, my brother, gave me his wooden suitcase. Mrs. Kotkowska baked some flat cakes for me, the size of her largest cooker ring. Mr. Kraska gave me half a loaf of bread. My sisters scraped a few marks together for me. In spite of it our neighbours refused to believe that I would be taken, in view of my recent bout of severe rheumatic fever. And though I was 13 years old, I was not well developed and was often taken for not more than 10. My parents’ friends kept consoling them, particularly my mother who was very distraught, that the medical board was bound to sent me straight back home. “It would be inconceivable,” they said, “even for the Germans, to send such small children for forced labour.”

Yet I had been given the day and the time to report to the Arbeitsamt and it was approaching irrevocably to the growing despair of my mother. I do not remember the exact day or even the month. I know that it was the early spring of 1942, the thaw had just set in, the snow was melting and ice had broken on the river. I did not want anybody to see me off, but on everybody’s insistence I agreed that both my sisters, who had to be at work by 7 a.m., came with me. Father, who started work at 6 a.m., was the first to say goodbye to me. Both my parents had spent the night sitting by the the kitchen range, crying, whispering to each other… At 6 a.m., carrying my small suitcase, I came out to the yard and was surprised to see some of the neighbours already waiting to say goodbye to me. First came Mrs. Kotkowska bringing me a pair of warm gloves made of pieces of thick fabric. She hugged me and kissed me, crying pitifully. The tears of this elderly woman caused others to surround me, crying and lamenting. Mother began loudly cursing the Germans for taking her child away. One of the men took her inside and tried to calm her down, explaining that gendarmes may hear her and arrest them all. But it didn’t help much. Trying to stop myself crying I clenched my teeth, but a moment later I was sobbing my heart out, as never before. Among this general lamentation they all saw me off to the highway. Even now, so many years after the event, I find it extremely difficult to describe this scene, as just recalling it brings tears to my eyes. That’s why I am writing it at night, when my wife and children are fast asleep.

My sisters walked with me, one on each side, and carried my suitcase in turns, telling me that I would have enough time later to get used to its weight. We kept crying, very, very softly all the way. As we arrived at the Arbeitsamt we discovered that mother, wrapped in a black shawl, had followed us like a shadow all the time, keeping out of sight.

A German clerk read out – in broken Polish – about twenty names and mustered us in threes. From that point on no relatives were allowed to follow. But my sisters did follow at some distance and mother even further behind. We were led by a tall slim German who could speak both German and Polish and escorted by a German gendarme. We marched along Sienkiewicz Street, across the Warta river bridge and the Market Place, then in the direction of another market, the one with the cinema. There, on a corner site, stood a synagogue, now burned out and derelict. We were brought inside and told to sit on the wet straw scattered over the floor. The gendarmes got busy now chasing away parents, who, like my mother, kept following us. Many in our group kept crying and to silence us our escort began telling us that we would be sent to a large estate with gardens and masses of flowers, whose owner was a very good man who loved children, childless as he himself was. In the afternoon another small group joined us. We were then told that those who lived locally could go home for the night, but had to be back by 6 a.m., or else gendarmes would go and bring them back by force.

I left promptly and practically ran all the way home. The first to see me was Mrs. Kotkowska: “So they let you go after all,” she said, not believing her own eyes. “Yes, but only until tomorrow morning,” I replied, glad at the prospect of another night at home. Mother already knew that we were not going to leave until the next day. One more afternoon, one more night with my loved ones! I did not want to waste my time sleeping, I wanted to enjoy every last minute at home. I did not even go out to see my friends or neighbours.

The morning was a carbon copy of the previous one: more tears and lamentations. This time mother took me to the assembly point. Father promised that he would stand at the railway crossing and wave to me. Once again, mustered in threes, we were marched under escort to the station and to the platform through a side gate, which was immediately locked, keeping out the desperate, crying mothers. Those who dared to come close to the fence were showered by the gendarmes with potatoes shed by some freight wagons. The mass lament reached its peak when the train from Kutno arrived on our platform. Now we also joined in the crying and the guards pointed their guns and threatened to shoot. The carriage was very crowded. To be able to look out I went to the toilet, leaned out of the window and called out: ”Mama, don’t cry! I shall be back!”

The train started on its way. I stayed in the toilet hoping to see my father. And indeed, as promised, he stood there waving by the lowered barrier at the Koło-Sempolno highway crossing.

This was my first time away from home and indeed my first ever train journey. We travelled for a few hours until we reached Poznań. The station seemed enormous to me, but dark and gloomy, shrouded in smoke. Our escort told us to get off the train and sit down on our bundles, while he himself disappeared, leaving in charge of us the only adult in the group, Józef Mijalski from Rychwał, a village in the district of Konin. He was being taken for forced labour with his 11 year old daughter, Helena.

Three hours later our escort returned, counted us and assured us that soon we would be continuing our journey. We boarded a train from another platform. For about an hour we kept going north until we arrived at the small station of Złotniki, where we got out again. We now walked in the westerly direction along a narrow paved road. After some 200 metres we saw a rider on a black horse coming towards us. On seeing him our escort became animated and asked us to practice the greeting: “We greet you gracious Sir!” As soon as the rider was close enough he gave us a signal and we called out the greeting in unison. The squire did not reply, but having come closer, obviously annoyed, he called out in bad Polish: “Damn it! They are all children!” Our escort, suddenly meek as a lamb, stuttered in reply that nothing better could be found. Rudolf Landgraff – such was the squire’s name – just turned his horse around and rode away. Before us lay Pawłowice, the village and estate that belonged to him.

Our group of children and teenagers originally numbered about twenty. Most came from Koło, but there were some from Konin and some girls from Łódź. The ones from Koło were: Stanisław Biliński aged about 16, Marian Idzikowski, 16, Kazimierz Szczesiak, 15, Jerzy Szczesiak, 14, Czesław Tomczyk, 14, Daniel Wietrzykowski, 15, Witold Stefanowski, 14, Mieczysław Zamiatała, 14, Zdzisław Przeor, 13, Jerzy Walczak, 13, Jan Stachura (might be Stachurski), 13, Tadeusz Sokołowski, 13, his sister Marysia, 14. There were two more girls, Czesława, 15 and Pelagia, 15, from Ruszków near Koło. The only adult was Józef Mijalski, from Rychwał near Konin, aged about 40, with his daughter Helena, 11. From the same area came Józef Pasik, 14 and one woman, Mrs. Starościna (or perhaps Starosta), whose husband had been killed in the September 1939 campaign. There were also a few girls aged from 15 to 25 from Łódź, but I remember only some of their first names: Helena, Krystyna, Irena, Honorata, Maria, Zofia, Prakseda. Later two men joined our group, Władysław Myszyński aged about 26, from Palędź, in the Poznań district, and Bogdan Elsner, aged about 17, also from the Poznań area. Soon after our arrival the Germans added to our group several nuns aged 38 to 55, probably from a convent in Poznań or its environs.

We were billeted in one of the halls of the local school. We were issued pallet covers, made of some paper-like material, to be filled with straw, but on the first day we received neither food nor blankets. We covered ourselves with our coats and jackets and we all shivered with cold in the morning. Reveille was at 6 a.m. Several of the older boys went to fetch the breakfast of coffee and bread – two slices per head, far from enough.

Next the estate manager picked two women for kitchen duties and the rest of us were herded in the manor’s courtyard, the site of the roll-call every morning. Then, depending on the season, in the summer at 5 or 6 a.m, and in the winter at 7 a.m., the sound of the steward’s iron rod hitting the ploughshare hanging from a wire by the gate would call us to work. Everyone was then meant to assemble, the locals on the left side of the yard and we, the newcomers, on the right.

On the first day the roll-call was honoured by the presence of the squire. He passed along the line, stopping to ask each of us our age. The answer had to be, for instance: “I am 13 years of age, my lord.” After this presentation the steward assigned the locals to various jobs and then he did the same with the more mature looking ones amongst us. The remaining ones, including me, were sent by the estate manager to the store. There we were each given a large basket and followed our temporary overseer – Mr. Gołaski – to the fields. In the first few days our task was to gather stones in the fields and take them to the side of the road.

Mr. Gołaski was a very decent man, like a father to us. In order to get to know us better he kept asking us questions: where did we come from, did we have parents, what were their jobs, etc. As soon as our parents were mentioned many of us burst into tears and then even our overseer could not hold back his tears. He cried with us and cursed the Germans. His heartfelt compassion helped us greatly at this difficult time.

The work in the fields was very heavy, while the food was poor. The nuns cooked us some kind of soup, such as barley or pea soup, borsht, bean, soya, turnip, sugar beet, or just potato soup or potato dumplings. In all the years I spent on forced labour in Germany not once did I or any of my mates have a piece of meat, sausage or even black pudding. I never had any milk. The soup was our main meal, while for breakfast and supper we were almost invariably given bitter corn coffee. Our daily ration of bread consisted of two slices, spread with either jam or margarine. Once in a blue moon we were given in the evening a gruel cooked with whey, or borsht or potatoes. Hunger made us steal potatoes from their heaps.

It was somewhat easier in the summer, when one could pinch some onions or horse carrots growing in open fields. While working in the fields we would often eat the raw cabbage, turnips or sugar beets. The worst time was winter and spring. The braver ones might steal into the barn at milking time and have a surreptitious gulp of milk. But woe to the one who got discovered by the cowshed overseer. Being a bit of a coward, I never dared it. Only the ones who worked in the cowshed were allowed to drink milk, almost as much as they wished. But there were not many volunteers for the job; you had to get up at 2 a.m., clean and feed the cattle, take out wheelbarrows full of manure, and milk the cows. Should one of the usual workers fall ill, it was usually either Marian Idzikowski or Kazik Szczesiak who had to step in, as they were nearly grown-up.

Personal hygiene on a day to day basis was difficult to maintain. There were no facilities for it. One had to look after oneself the best one could. Shirts, underwear, trousers, sweaters, socks, shoes, were all wearing out and there was no chance of replacing them. All clothing was rationed and though we were apparently entitled to the necessary coupons, we never actually got them. Nor were we issued with work clothes. We had no access to soap. And for how long can one expect a thirteen year old child to keep clean without an adult’s care?

These were the conditions offered to us by the squire of Pawłowice, Rudolf Landgraff. We went about dirty, the dirt penetrating deep into the skin. We all had lice and fleas and our room was infested with bedbugs. The vermin kept devouring us alive and even after a hard day’s work it was not easy to go to sleep. Every scratch of the head brought out a louse; lice lived in every seam of our clothing. Day and night we scratched with dirty nails until we bled. That brought even more of the bloodsucking insects out. Nowadays people have no experience of the revolting feeling of being devoured alive by lice or bedbugs, while we in Pawłowice, in addition to the hard work, were forced to coexist with those parasites round the clock. Dipping oneself fully clothed in water did not help. Laundering one’s clothes without soap and without boiling them was not much use. Rubbing them with sand or clay while laundering did not help either – the insects survived it all.

We, children, had to work alongside grown men. Quite quickly they taught us to work with horses and oxen. Oxen were the worst, as during ploughing they would just lie down and refuse to pull the plough. This happened again and again, and should the German supervisor find a field only partly ploughed, he would whip us, not the oxen. Nevertheless, quite soon we became fully trained farm hands. We were not paid for our work, all we were given was the miserable food which left us permanently hungry. Whether one was allowed to be ill and stay in the dormitory depended wholly on Herr Landgraff’s mood. Should he notice many missing during the morning roll-call, he would search for them in the billets, kick them out of bed and whip them mercilessly.

Once I was sent to spread artificial fertiliser on a very windy day. After the day’s work I was hardly able to see. In the evening I washed rather perfunctorily in cold water without any soap. In the morning I could hardly open my sticky eyes. I decided to go sick and stayed behind. A couple of hours later Herr Landgraff arrived in our room, this time holding a walking stick. Having probed all the beds with it, he finally found me. He hit me several times and told me to report to the estate manager. The latter handed me a small piece of sheet metal and ordered me to scrape out manure from between the stones making the floor of the dungpit. After that, even when feeling genuinely ill, I would go to work rather than risk a beating.

Towards the end of the 1943 harvest I was working on threshing the rye from the ricks. My job was to receive the threshed and pressed straw; I could not manage it, the work was beyond my strength. Suddenly I felt faint and noticed that my nose was bleeding. I cried out. The machine was stopped, a man climbed up the straw and carried me down. Some people suggested that I might have strained something, placed me on a trailer and took me to the barn. The nuns working in the kitchen took care of me. After three days’ rest I went back to work, to avoid a kicking by the Germans.

Here, in the Poznań area, Poles did not have to wear the “P” patch, but even so the Germans managed to recognise us. One day I went on foot to Poznań. I was walking down Libelt Street. Past the railway bridge I noticed a gendarme; he called me to him and without saying a word slapped my face and continued on his way. Why did he hit me? Because I was a Pole? But how did he know it? But then, who would look so scruffy apart from a Pole?

Something similar happened to me in Pawłowice. One day I was coming back from the fields carrying a basket with several large potatoes for potato pancakes. As I reached the village I noticed a gendarme riding a bike towards me. He stopped, called me over to his side and without a word hit me so hard that I fell over and the potatoes scattered over the ground. The Kraut then mounted his bike and just rode away. I wondered how he knew about my stolen potatoes which were well covered in the basket. It was only later that Władek Muszyński told me that in both cases I was beaten because I did not to bow to the police. From that time on I bowed to every German, whatever uniform he wore.

It was early autumn 1943. The eastern front was proving increasingly costly and the Germans needed more and more manpower in their weapons industries. Rudolf Landgraff received a request for a contingent of workers to be sent to the Poznań Arbeitsamt. Preferring the devil they knew to the one they did not, people got scared. The stewards had a problem. They did not want to antagonise the locals and decided to send instead the “seasonal workers”, as we were being referred to. Herr Landgraff, concerned with the efficiency of his estate, ordered them to pick the worst workers amongst us.

Consequently the following were selected: Jurek Szczesiak, Mieczysław Zamiatała, Zdzisław Przeor, Józef Pasik, I, and one of the locals, Władysław Łaganowski. In the Arbeitsamt they did their own selection. As I learned later, Mieczysław Zamiatała and Zdzisław Przeor were sent to farms in the depth of the Third Reich. Zdzisław Przeor eventually returned to Koło, but to this day I don’t know whether Mieczysław survived the war. Jurek Szczesiak was sent to work in the DMW factory (Zakłady Cegielskiego) in Poznań.

Józef Pasik, Władek Łaganowski and I were sent to the Focke-Wulf aircraft plants, first in Poznań and then in Krzesiny. We were assigned to different groups, so to begin with I was not aware that we would be working in the same factory. First we were taken to the bath/delousing station in the Górczyna barracks. We were told to undress and were taken stark naked to the showers where we had to scrub ourselves with some kind of powder and soft soap. It was already very cold when the guards led our large group along some streets to a brick building, seemingly a former school. I noticed a similar red brick three-storey building on the other side of a courtyard. An iron fence surrounded both buildings and the gate was guarded by a soldier from a Luftwaffe servicing unit.

I was billeted in a hall on the second floor with windows facing Maria Magdalena Street. Józef Pasik, my mate in Pawłowice, was unfortunately assigned to different quarters. Władysław Łaganowski was lucky, as he could stay at his sister’s in Poznań. And so again there was no one I could rely on. There were about twenty of us in the hall, aged roughly from 10 to 25. Just one man, named Walczak, the same as I, was older, around 50. Some of the people came from Włocławek and from Inowrocław. We slept on bunk beds with straw-filled pallets. Each floor had its own guard, and that was in addition to the guard at the gate. In the mornings and evenings the guards doled out two slices of bread per head and bitter black coffee. It seemed like a kind of prison to us.

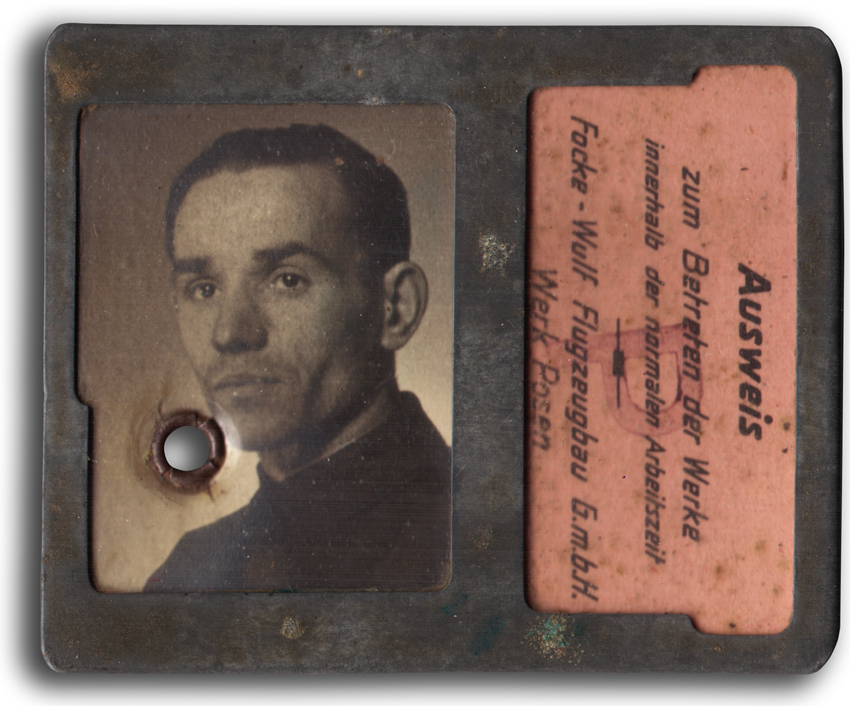

Ausweis (identity document) for a Polish worker at the German Focke-Wulf aircraft factory in PoznańAt the beginning of 1944 we had to leave these buildings, now needed by the Wehrmacht, and were moved to part of a hall in the Focke-Wulf plant located on the present grounds of the Poznań International Fair. The main aircraft plant was in Krzesiny. The present no. 2 hall of the Poznań Fair served as quarters for hundreds of workers, of whom some were employed locally, but a great majority commuted to Krzesiny. The present administration building of the Fair housed the army units guarding the plant. The training workshops were located immediately to the right of the main entrance, while some aircraft parts were produced in the Świerczewski Street hall. The domed hall was used for the storage of beetroots, potatoes, carrots, turnips and cabbage, and bore little resemblance to the present no. 11 hall. The working and living conditions in Poznań were much worse than they had been in Pawłowice. Poznań was for me a horrible, gloomy city, full of Nazi soldiers and Gestapo men. Besides I did not know the city and was constantly afraid of getting lost. I was among Poles, of course, but they were strangers and mostly much older. They kept asking me where I came from, whether I had parents, why was I so emaciated and dressed in rags and whether I might be ill. Sometimes one of them would give me a chunk of bread.

Ausweis (identity document) for a Polish worker at the German Focke-Wulf aircraft factory in PoznańAt the beginning of 1944 we had to leave these buildings, now needed by the Wehrmacht, and were moved to part of a hall in the Focke-Wulf plant located on the present grounds of the Poznań International Fair. The main aircraft plant was in Krzesiny. The present no. 2 hall of the Poznań Fair served as quarters for hundreds of workers, of whom some were employed locally, but a great majority commuted to Krzesiny. The present administration building of the Fair housed the army units guarding the plant. The training workshops were located immediately to the right of the main entrance, while some aircraft parts were produced in the Świerczewski Street hall. The domed hall was used for the storage of beetroots, potatoes, carrots, turnips and cabbage, and bore little resemblance to the present no. 11 hall. The working and living conditions in Poznań were much worse than they had been in Pawłowice. Poznań was for me a horrible, gloomy city, full of Nazi soldiers and Gestapo men. Besides I did not know the city and was constantly afraid of getting lost. I was among Poles, of course, but they were strangers and mostly much older. They kept asking me where I came from, whether I had parents, why was I so emaciated and dressed in rags and whether I might be ill. Sometimes one of them would give me a chunk of bread.

In the initial two or three weeks I was placed in the training workshop, where all day long I had to saw aluminium sheeting into squares. The working day was 12 hours and the results of our endeavour were checked by foremen. While we lived at Maria Magdalena Street the guards woke us at 5.30 a.m. Afraid to use the tram in case I would not know where to get off, I would walk to the present Marchlewski Street and along the cemetery, which is no longer there, and then across the Station Bridge.

Following the short training period we were sent in small groups to the Krzesiny plant, which one reached by the special workers’ train. To get there by 7 a.m. one had to get up at 5 a.m. The plant was spread over huge grounds with several interconnected halls and a number of separate buildings. We had to cross several passages, one after another, each carefully guarded. Every worker was issued with an Ausweis, an identity card with a photograph, marked with the symbol of the particular hall he was working in. One was not allowed to enter any of the other premises. Our papers were checked on entry and on leaving and we were randomly searched, as some of the Polish workers secretly made themselves aluminium rings, combs, etc.

I worked in the middle hall, where aircraft wings were being made. In one of the end halls separate wing parts were cut out of metal sheeting, which were then brought on handcarts or on battery operated carts to our hall. Our job was to fit them into their proper place of the pre-prepared skeletons, a kind of scaffolding, to be riveted in. Before, though, these large sheet metal pieces had to be made to fit by sawing or filing. The foreman would mark the correct points for the rivet holes, which were then drilled for cold riveting. Next, the wings were passed to the technical control foreman and subsequently for further treatment, like insertion of cables, etc. In the neighbouring hall fuselage was produced through a similar process; my friend from Koło, Tadeusz Zając, son of a basketmaker from Toruńska Street, worked there. The parts were then transported to the main hall to be assembled as finished aircraft minus the engine. The engines were installed somewhere else. If I remember rightly, each shift produced two to three aircraft, which were then loaded on trains on a dedicated sideline, the wings arranged along and at the sides of the fuselage. There were three other workers at my workbench and a foreman, a Pole from Gniezno, whose name I do not remember and that also applies to the other three. There was no time to get to know one another. One was never out of sight of a German foreman or a guard. The place was very noisy and fear was never far away. It was difficult to communicate, even when working at the same workbench. It was unthinkable for a Pole to stop for a moment and exchange a few words with a mate.

The factory was working 24 hours a day, on two 12 hour shifts, seven days a week. We had no days off, apart from two-day holidays, such as Easter, when we had the first day off, and back to work on the second day. During the 12 hour shift one was allowed only 10 minutes for breakfast and 30 minutes for lunch. The same conditions applied to the night shift. The breaks seemed to pass in a flash even though there was nothing to eat, as the two slices of bread spread with either jam or margarine given to us in the morning were invariably consumed on the way to work. The main meals were simply awful, consisting of a thin soup of either turnip, cabbage, red beetroot or mangel-wurzel (large beets used as cattle food); it was a matter of luck whose tin bowl of soup would contain a piece of carrot or potato. The only addition was a slice of black bread.

My training did not prepare me for the work in hand. In the training workshop I was just sawing pieces of sheet metal, while here I had to rivet together parts of aircraft wings. To begin with I was even scared to handle the tools, in case I spoiled something. The Polish foreman placed a small steel block in my hand and guided my hand to under the rivet just at the moment when the pneumatic hammer in the hands of the man above pressed the rivet down. The work called for some precision and co-ordination of the two workers. I managed while the foremen guided my hand, but after he left, it all turned out wrong. My rivets were crooked and shapeless, the foreman had to remove them and I had to start all over again. Even the second attempt rarely succeeded. I shall never forget my work on that first aircraft wing.

The German control foreman marked my rivets with red chalk and then called me. He grabbed the clothes round my neck and, cursing all the time, kept hitting my head and my back against the rejected wing. I did not cry, I did not say a word, I was only praying to God for the wing to come off in the air with a Nazi pilot sitting at the controls. My Polish foreman, having witnessed the scene, began to teach me all over again on used bits of sheet metal and eventually I did learn the craft of drilling and riveting.

Józef Pasik, my mate from Pawłowice, worked in a different department and only occasionally did I come across him. I saw Tadeusz Zając more frequently, as he worked in the neighbouring hall on fuselage assembly. Unlike me, he did not live in a dormitory, but had a tiny windowless room on Gąsiorowscy Street. One day we were leaving the day shift in Krzesiny together, when he took me to his quarters and gave me a loaf of stale bread. This was the only time during the 1941-1945 period of forced labour that I held a whole loaf of bread in my hands!

Those among us who lived privately received their own ration cards, they also had a better chance to visit their parents on a free day. Thus, having some help from home and being in charge of their own rations, they were able occasionally to share their bread with friends. While I was still billeted in the school building on Maria Magdalena Street, one mate (Stawicki or Sawicki, from Kujawy) gave me quarter of a loaf of country bread which was partly mouldy. I ate it straight away while on my way to the night shift in Krzesiny. I became sick at work and felt very weak. The supervising German foreman sent me home. I slept through the night and the following day, having had only one slice of bread with black coffee to eat. In the evening, though feeling ill, I went to work, as in my billet there was no doctor who could certify me sick.

While working in Krzesiny I had constant trouble with my feet. My heels were very painful, to the point that I could not put pressure on them while standing. I managed sometimes to get a seat on my way to Krzesiny and that gave my feet some rest. But I was usually told by some older man: “You are young, sonny, you can stand.” And nobody believed me when I tried to explain that my feet hurt me.

Air raid warnings became quite frequent and every worker running to the shelter had to take with him the tools which he was handling at the time. I remember the allied air raid on Poznań on the first day of Easter 1944, one of the few days when I was off work. I was at that time billeted with many other workers in the no. 2 hall of the present International Poznań Fair. Suddenly about noon the air raid warning was sounded and the guards chased us to the shelters in the grounds of the cemetery next to the Fair grounds, between the Święcicki and Grunwald Streets. The bombing started within minutes. It was frightening yet welcome – at last even here the allies were giving the Germans a good hiding!

Sand began to shower us in the shelter, but the iron doors were bolted and guarded. Suddenly the whole shelter shook, the lights went out and water began to pour in from a broken pipe. The guards then opened the door and moments later the all-clear sounded. A terrifying picture met our eyes. Almost all the production halls were on fire. The only ones which were left standing were the hall serving as billet for many workers and the building which now houses the administration of the International Fair. The allies must have had good intelligence where to strike and what to save; they had also chosen a non-working day.

The destruction of the Focke-Wulf plant on the present International Fair grounds left the Germans confused and disorganised. There were now no guards at the gate, nobody was being checked. After the initial shock they started sending us to clear the rubble.

Taking advantage of the disorder I left the factory grounds, meaning to have a look at the damage of the Main Railway Station, but seeing the enormous hole right through the Station Bridge I gave up the idea. Then it struck me that I might visit Pawłowice and share the welcome news of the destruction of the plant with my mates. They were shocked by the way I looked and thought that I was ill. The ‘seasonals’ fed me plenty of soup, and the local Poles brought me bread. They all wanted to hear about the raid on Poznań.

On the second day of Easter I was due to go to the Krzesiny plant. However, convinced that there would be no trains because of the bombing, I worked out a good reason for my absence. I would tell the Germans that on the first day of Easter, my free day, I went to Pawłowice, planning to return in the evening, ready for work the following morning. But I was told at the Złotniki station that Poznań had been bombed and that no trains were running.

I managed to walk to Poznań on the day after Easter, having thus missed two working days. There was no one in the hall where we were sleeping, but there were some additional bunk beds. My wooden suitcase, with all my belongings, was nowhere to be seen. Someone told me that everyone had been moved to Krzesiny, where several days ago we had noticed barracks fenced off with barbed wire being put up. Now I was assigned a place in one of them. This was now to be the plant’s work camp. And once more I found myself among total strangers.

Some people living in the barrack worked on the night shift, others on the day shift, so that sleeping was quite impossible. Everyone was dead tired after work and there was little chance of getting to know anyone. All one was ready for after the heavy work was bed. Should one go about walking in the camp, one risked being picked by guards for additional jobs. If there were any urgent jobs to do, they would get us up day or night .

Here in the Krzesiny camp we were each given only one slice of bread in the morning and evening and for lunch the soup was the same as before – it simply could not be made any worse. We were not allowed out of the camp except to go to the factory. We did not write any letters and did not receive any.

However the epilogue of my Pawłowice escapade was still to come. After about two weeks in the camp the foreman told me to report to the office in the factory hall. There was a queue of men waiting in silence and I joined it. Many arrived after me. Every few minutes one of them would come out having been ‘dealt with’ and the next one went in. Some were leaving with tears in their eyes. But they did not say anything, they gave us no warning. People were silent because most of us knew what to expect. “My God,” I thought. “What next? These days one has to queue even to be whipped.”

And then my turn came. I entered a small office. Opposite the door was a desk, on the corner of which sat a tall, young Gestapo man in a black uniform. In his hand he held a whip, a metre long, made of plaited black hide. In the middle of the room stood a wooden box about 20-30 cm high. A blond, blue-eyed girl of about 18 stood behind the desk next to the Gestapo man. She had tears in her eyes. She was the interpreter. The Gestapo man asked me why I had missed two days of work. I gave him the explanation I prepared. He swore at me and told me to lie down on the wooden box. I tried to cover my bottom with one hand, but he just kicked it away and by that time I gave up. He hit me once saying, “ein Tag,“ one day, and then hit me again, saying “zweiter Tag,” the second day. He then told me to get up and to thank him for the whipping.

I did not start to cry until I was back at my workbench, when the Polish foreman asked me what I had been called for. For several nights I had to sleep on my belly.

But that was not all. A week later the same Poles were all called to assembly in the square between the factory halls. We were mustered in a line and addressed by another Gestapo man. He said that should anyone miss another day of work, one Pole a week would be hanged in every hall. I froze at these words. He then added: “That’s not all. Some of you will now come with us in this vehicle.” One of the Gestapo men ordered us to count off along the line. Every tenth man was dragged out. No one dared to move, or to look right or left. I was the seventh… I shall always remember that awful moment of this counting off. While we were standing, the selected men were loaded on to a lorry and taken for two weeks to the penal camp in Żabikowo. Not all of them survived.